For any country that wants to grow an adequate and stable food supply, some level of irrigation is necessary. Even in the Upper Midwestern U.S., where there is ample rain-fed cropland, we count on irrigated acres to provide stable crop production, especially in drought years. As recently as 1988 and 2012, corn and soybean yields in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana tanked, because of droughts. The U.S. food supply would have been on unstable ground in  those years, without the irrigated areas in the Great Plains.

those years, without the irrigated areas in the Great Plains.

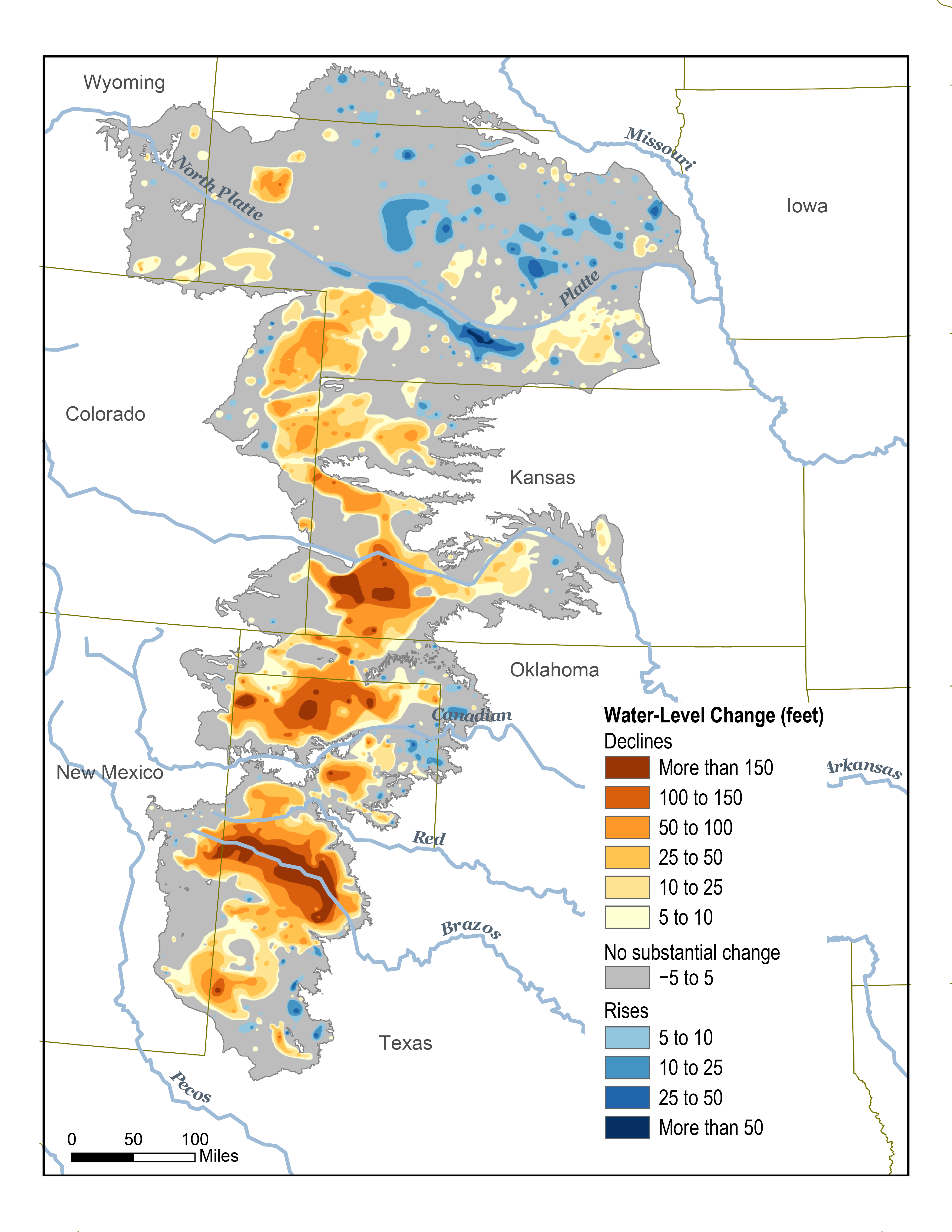

The Ogallala Aquifer, underlying eight states in the Great Plains, supports nearly one-fifth of the wheat, corn, cotton, and cattle produced in the United States. However, it is widely reported that water from the Ogallala Aquifer is being extracted faster than it is being replenished in some areas. Because it is a non-renewable resource, the Ogallala Aquifer, and others like it, should be conserved.

It is possible to conserve these important nonrenewable water resources, like the Ogallala Aquifer, and still protect the U.S. food supply in drought years, by irrigating the Upper Midwest. While this may seem like an irrational idea and waste of resources, let’s take a closer look at how it could be accomplished.

The Upper Midwest often receives excess rainfall, resulting in flooding of high value metropolitan areas. In fact, in most years, flood events are more prevalent than droughts. To mitigate flooding, cities often look upstream to locate and build structures to store excess water and reduce flooding. In times of drought, the same water retention structures could become the water source for drought-stricken cropland. This seems like an excellent way to build a more resilient landscape; capturing water during periods of excess and using it in times of need.

Multiple revenue streams could be used to finance the dual-purpose water retention structures. Those farmers interested in spending money on irrigation systems, coupled with reductions in federal crop damage premiums, could offset the cost of the impoundments. Downstream, the beneficiaries of improved flood control could also help pay for a percentage of water retention structures.

In 2012, Jim Sladek, a Southeast Iowa farmer, said his irrigated acres out-yielded his non-irrigated areas by 120 bushels per acre; the profits of which paid for the original irrigation system – in just one year. In 2014, Sladek built an 18-acre pond for another irrigation system. Jim is still making adjustments, but he is confident he can increase yields by 50 bushels/acre/year, on average.

Sladek says, the harder farmers push to produce more, the higher the risk of something going wrong. Irrigation is one input that should improve yields and lower risk. There are few inputs, other than water, that can make this claim. For this reason, he is excited about irrigation in the Upper Midwest.

As an alternative to pumping nonrenewable resources dry like the Ogallala Aquifer, why would we not consider using water from flood retention structures to irrigate Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana?

Honoring the Past

Honoring the Past

My first reaction is questions. How big would these impoundments be? I am wondering in part because of the mention of flood control.

The City of Ames, over the past few years, went through a long complicated flood-prevention study that included looking at possible upstream rural impoundments. It turned out that building the numbers and/or sizes of impoundments that would be needed to have a really significant impact on flooding would have serious environmental costs, apart from the also-major financial costs.

And one of the big possible impoundments, the previously-pushed-by-Neal-Smith “Ames Reservoir,” would be an algae-filled polluted mess because of the large, highly-rowcropped watershed. It would not be a good outdoor recreation opportunity.

Or would this irrigation proposal mean more small ponds? I’ve personally seen that even fifteen-acre or twenty-acre ponds can drown natural areas in a state that has less of its original landscape than any other.

Of course it’s generally perfectly legal for landowners to build their own ponds, using their own money, no matter what gets drowned. But I would not be enthused about using my tax dollars to fund more impoundments in Iowa unless there were a strong enforceable guarantee that one result wouldn’t be yet more net loss of permanent vegetation in this state (including prairie remnants, pastures, woodlands, and wetlands). And I would also want the publicly-funded sites proposed for drowning to be first surveyed for rare and listed species.

Cindy, thanks for your thoughtful comments. I agree there are a lot of moving parts. I certainly don’t have all the answers. It is a solution that Iowa State, University of Illinois, and Ohio State have all looked at. It is my option the retention structures would be installed on drainage areas of 200 to 500 acres; being more localized instead of one large reservoir. And yes, it would take a lot of these retention structures, but if we could strategically place they we could help communities with recurrent flooding.

Whether these retention structures are wetlands or ponds is a function of the landscape. In a flat topography they will be wetlands and in steep topography they will be ponds. Unless we excavate or fill, the landscape will always decide. Typically, it is cheaper to store water in ponds (vs. wetlands) because the increased water depth of ponds requires less land.

The ponds/wetlands would serve as a water filter for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment. That is one of the beautiful things. They are multipurpose; filtration, flooding, irrigation, and habitat. We probably had less water habitat than ever before on the landscape of Iowa. I understand the concern about losing habitat, but I feel they would create more habitat than they destroy. You concern for T&E species is valid and would have to be taken into concern.

With climate change this problem of flooding is only going to get worse. Every plan has it shortcomings.

Thanks, Tom. You make interesting points, and I appreciate your taking so much time to respond.

As I’ve watched Iowa over the past forty years, I’ve seen, again and again, original natural areas being destroyed. Some of that has happened via the building of what some conservationists call “fake lakes.” And when “steep topography” areas are turned into bodies of water, the likelihood of natural-area destruction goes up. Steep areas, along with very wet areas, are where original ecosystem fragments, especially prairie remnants, are most likely to still be hanging on.

Of course it’s true that if a steep prairie remnant with a couple dozen native species is submerged by a new pond, that pond can then be surrounded by a new prairie planting and that planting will be wildlife habitat. But very often, the new planting will consist of the twenty-five or so common native species that are typically used in CRP plantings. Meanwhile, some of the species that were lost will be those that are mostly found only in original prairie remnants and are rarely found in plantings. Those tend to be species that are declining.

I’ve talked with a few landowners who learned about prairies after building ponds on steep topography. Looking back, they realized too late that they had probably drowned some of what they had come to value. Habitat area is not the same as habitat quality. A hillside prairie remnant that has prairie violets and hoary puccoons can’t be ecologically replaced by a pond-side planting that has only common flowers like black-eyed susans.

My tax dollars are often used to subsidize ecological degradation. It seems to me this irrigation proposal could easily turn into one more way that happens. And I am concerned about declining species as well as species that are finally legally listed because they are about to go over the brink. We end up with listed and extirpated species by ignoring declining species.

Other thoughts occur. Your original post started with a statement about how, around the world, irrigation is necessary to ensure adequate and stable food supplies. But in the case of the Upper Midwest, a lot of the corn and beans are exported, directly or indirectly. To what extent would taxpayer-subsidized irrigation ponds be subsidizing ag-industry profits, rather than helping to ensure that all Americans have sufficient calories and nutrition?

Also, one way to make crop fields more resilient to drought is to maintain healthy soils with good structure and high levels of soil organic matter. That does not describe most conventional rowcropped soils in Iowa. Would farmers who benefited from subsidized irrigation be required to achieve and maintain high-enough SOM that their soils could better store and release whatever rain does fall? Or would they be required to at least use cover crops on all their rowcropped acres and/or use extended rotations, and be required to follow a conservation plan that includes water-quality protection?

Also, I don’t really understand how irrigating the Upper Midwest would help protect the Ogallala Aquifer. Perhaps there would be a national policy that basically says “We’re going to subsidize irrigation ponds in the Upper Midwest to help ensure the commodity crop yields in that region are high every year, thereby helping Upper Midwest farmers. Meanwhile, you farmers and other residents of the Ogallala Aquifer region will now be expected to protect your declining aquifer and stop drawing it down so fast.” If so, I’m pretty sure the outraged screaming from the Ogallala region would be heard all the way to Vermont.

Finally, I hope that the universities that are looking at this irrigation idea are looking at all aspects of it, including the ecological impacts. Thirty years ago, I would have assumed that would automatically happen. But I’m not so naive about university research anymore.

Cindy, I appreciate your love for the prairie. We have lost more of our native prairie than any other ecosystem. The plants that gave us the dark rich topsoil are now the most endangered ecosystem. It is crazy. I understand your desire to keep every remnant. I do feel the best thing we can do for our prairies is to stop the invasion of woody vegetation (trees and shrubs).

I do understand you concerns. Just because we can raise a more reliable food source with a more resilient environment, it doesn’t mean that they will stop irrigating in the Ogallala region. In one of my past posts I wrote about the research that showed when farmers we given tools to improve the efficiency of water use, they just used the water somewhere else. It did not reduce the total drawdown of water. I understand your concerns.

Instead of building more earthen structures in a futile attempt to control nature, why not restore natural systems (woodland, wetland, prairie)? Instead of doing everything humanly possible to speed the movement of water off the land and downstream, why not let nature have a chance (once again) to slow that process. We are loosing top soil at 10-20 times the rate it can be replenished in order to satisfy the wants of a high input, unsustainable culture. Many suggest a dramatic decrease in human population. Eliminating our huge entourage of domestic animals is certainly an alternative. Reducing energy consumption is another. During an October 2018 gathering at ISU a group was asked to estimate the multiple of human consumption in Iowa vs Earth’s capacity for renewal. Wendy Wintersteen immediately said eight times. Based on our state’s loss of top soil her estimate was probably low. Robert Rodale once said that Iowa could raise enough food to feed itself in backyard gardens. What we in Agriculture are doing (trying to do) is feed a huge inventory of domestic animals and satisfy an insatiable appetite for motor vehicle fuel. The word sustainable has been so abused as to be almost meaningless. But I prefer to believe it is possible to create a wilder, more beautiful, more biologically diverse, and a more enduring Mississippi River Watershed. If Consumers, academia, and government create a low input, sustainable culture producers will respond spontaneously by creating a low input, sustainable agriculture. Any plan which does not meet the test of eco-efficiency is a betrayal of future generations.

Roger, all really good points if we are ready transform civilization.