It’s about time! Everyone knows that increased regulation always solves the problem. ~ quote penned by Tim Eshleman, sarcastic brother-in-law.

Recently I wrote a post that encouraged ag retailers to assist farmers with future regulations. Since then, I have been asked for my opinion several times on regulating agricultural pollution. As I ponder this question, I find the answer is complicated. First, let me go on record by saying that I absolutely believe farmers need to reduce soil erosion and improve water quality. The science is crystal clear. Farmers cause a significant portion of these problems, not only in the Midwest, but across the nation. Farmers need to do more and they need to do more now. Not just some farmers, but all farmers, not 10 years from now, not 5 years from now, but right now. So what is the solution?

Our voluntary approach is a failure…

On April 27, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation Act; legislation that took aim on reducing soil erosion. After 80 years, we are still trying to get it right. Conservation agencies have spent untold dollars on staffing and incentive programs. And we are still just chipping away at the problem.

Anyone who says the pathway to successful conservation is through a modest increase in costshare dollars or government staffing is clueless. And, the idea that “more of the same” solves these problems is complete and utter nonsense. It doesn’t take an Albert Einstein to realize doing the same thing over and over again, expecting different results is the definition of insanity. If the only path forward is the status quo voluntary approach, then I pronounce the voluntary approach as a failure and reject it completely. But where does that leave us?

The regulatory approach…

As I talk to people, there are two completely different reasons given for wanting to regulate agriculture. First, some individuals truly believe regulations will lead to real environmental change. And second, some individuals want to take punitive actions against farmers. As one environmentalist recently told me, “I am tired of fighting with agriculture. If farmers don’t react to the voluntary method then let’s just regulate the bastards.” To those of you who want to “regulate the …” hey, I get it. I really do. Everyone who feels they have been ignored wants to fight back. But spite and malice doesn’t solve problems.

I have to agree with Howard G. Buffett, an Illinois farmer and son of billionaire Warren Buffett. “Regulations never work well.” This is confirmed by the research of Michelle Perez. Perez says, “Given the “insidious” nature of nonpoint-source pollution, inspectors cannot easily detect and attribute nutrient pollution to a specific farm; nor can they easily determine whether a farmer is following a certified nutrient management plan or other management-related practices. Farmers who do not believe that following the nutrient recommendations in their plan would produce an economically viable crop or are too risk averse to give it a try are not easily regulated.”

If I thought the regulatory approach worked I would be more in favor of more regulation. But honestly, I think agriculture is too complex to be regulated effectively. And NO, this is not a cop-out for doing nothing. Again, farmers absolutely need to do something now. But personally I don’t want to get 15 years from now, with all the bloodletting that will come from regulation, only to find out we created a great paperwork system that had no effect on advancing soil and water conservation.

So what is the answer?

It is obvious the current delivery system for voluntary conservation is broken. However this does NOT absolve farmers from their responsibility of protecting the environment. Farmers cannot simply stand back and blame their poor environmental performance on the lack of costshare dollars and technical assistance. The burden of fixing the “system” rests squarely on the shoulders of agriculture. Farmers need to encourage the agricultural leadership to lobby for and develop a better voluntary system that can effectively serve their needs.

I encourage agricultural leadership to do the right thing. Design and enact a voluntary conservation delivery system that will bring effective change. I must admit I don’t know exactly what this new system looks like, but I know the success lies within the private ag retail system. Ag retailers must be a part of the solution. If ag retailers don’t get involved and the status quo continues, farmers will certainly face regulations. Regardless of whether these regulations are enacted out of good intentions or for punitive reasons, farmers will be stuck with these regulations.

Agriculture can do better. Agriculture must do better.

Ag’s Impossible To-do List

Ag’s Impossible To-do List

Enjoyed reading your article Tom. I agree, if we wait too long we will wake up some day and realize we allowed bureaucrats to string this out only to end up doing nothing. I am currently fighting an audit with the NRCS at the national level. Truly in bureaucratic fashion, because I did not apply hog manure on a tract of land ( which had as an inhancement that it would be knifed in) the entire contract is being kicked. Here I am trying to do the correct environmental practice and because I didn’t apply the manure in the first place, some bureaucrat determines I violated my contract. This is what drives farmers to fight any type of regulations. Dwight

That is troubling Dwight – but quite expected when we rely on a practice-based incentive rather than an outcome-based system.

Tim, I absolutely agree with this assessment.

To envision a better system, think about how many stakeholders contribute in a symbiotic way in producing the abundance of crops. Insurance, government, market, and academia are in alignment addressing risk, support, price and research toward the common goal. Farmers are rewarded in the policy and market arenas.

To produce abundance of ecosystem services (cleaner water, healthier soils, etc) the same alignment must occur. Enough demand already exists for sustainability, but the market, government and society are not yet ready to see the “symbiotic demand” solution.

Obviously, Tom, it’s impossible to regulate nutrient management because there is no reasonable way to verify compliance. But it would be easy to mandate other practices that, according to the science, would contribute measurably to the nutrient reduction strategy. Strategically-placed restored wetlands, buffers along all streams in the state, cover-crop plantings, grassed waterways, and various forms of conservation tillage all could be mandated and verified as in place and functional from year to year with relatively little effort.

Max,

I would like to think that if we had a good delivery system for voluntary conservation it would significantly reduce our need for regulation. However I place the burden of changing this delivery system on agriculture. It is not society’s problem to fix this. If agriculture believes the system is inadequate, they need to change it. Agriculture has an incredible lobby system. They need to put it to work.

I do agree if we are going to regulate conservation, then we should regulate things that we can easily monitor. Of course, if we are going to require wetlands, we need to fairly compensate landowners. I can imagine a situation where a landowner is not causing a disproportionate amount of nitrogen loss, but because of his landscape, he is required to put in a 10 acre wetland. This, of course, would place a significant burden on the landowner and be unfair. Of course as you say, the easy things to regulate would be tillage and cover crops.

Max, these points are well taken and make sense. Initially, as Tom mentions, cost reimbursement might be warranted for some land retirement; this could occur on a phase-in or phase-out basis. However, like ownership of other properties, land value is based on return and limitations of use. Tax payers should not indefinitely make payments for land that has selected practices associated with it; these should become part of the property and property value. Soil and water are natural resources belonging to society. People/farmers own the right to manage and make a living from them; they do not own the right to destroy or degrade them. Expecting/requiring some level of management performance seems both wise and realistic.

Your observations are well taken. Perhaps, you can have it done in your countries. Things are so bad in other countries and more so in India. We do not have anything like regulations at Govt level or at the farmers level pertaining to their farming practices toward pollution aspect. I wish , our countries learn from experience in western world. Keep on and set the practice. We may follow. Good luck.

What would happen if we actually enforced conservation compliance?

Kevin,

I don’t know that Conservation Compliance has ever been aggressively enforced, but certainly there was a time that it was enforced more than it is today. At last week’s SOIL meeting (Drake University) Craig Cox showed some pretty significant reductions in soil erosion that was gained by Conservation Compliance. I will try and get those statistics from Craig.

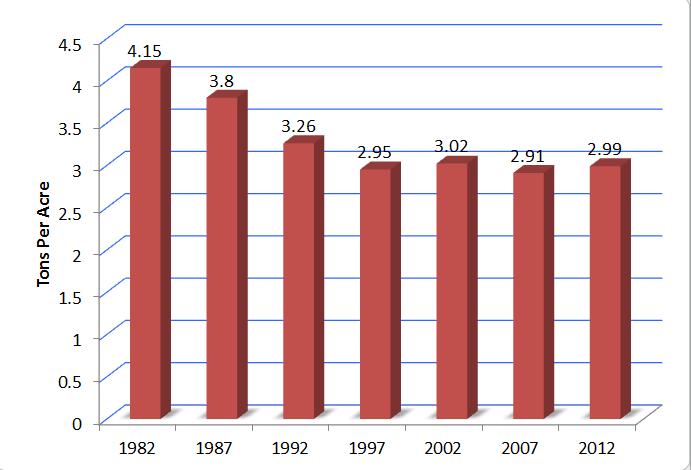

Estimate soil erosion declined 40 percent nationally between 1982 and 1997, according to the National Resources Inventory. An Economic Research Analysis of those data found that conservation compliance alone accounted for 25 percent of this reduction. Wetland losses declined dramatically under swampbuster as well. Agricultural conversions averaged more than 235,000 acres annually just prior to enactment of the 1985 farm bill. Conversions dropped to an average of 27,000 acres annually in the 1992-1997 period, once swampbuster was put in place and a degree of enforcement occurred.

Last week Craig Cox, EWG, provided this information last week at the Sustaining Our Iowa Land (SOIL) Conference. This conference was hosted by the Drake and the Agricultural Law Center. These are national statistics on soil erosion. By 1995 farmers with Highly Erodible Land (HEL) were required to fully implement a soil conservation plan. From this information, it is hard to argue that Conservation Compliance didn’t have a significant impact on reducing soil erosion.

By 1995 farmers with Highly Erodible Land (HEL) were required to fully implement a soil conservation plan. From this information, it is hard to argue that Conservation Compliance didn’t have a significant impact on reducing soil erosion.

This discussion is overlooking the rapid advancement of sustainability criteria being set by big ag commodity market players like WalMart. They are representing their customers’ demands for more sustainably produced food and fiber, and will likely have an impact in this arena. The customer drives the market.

Excellent point Les. Although I do think some people are tired of waiting for change. They are tired of future promises. They want effective regulation now. The sustainability program through food companies, although powerful, will take some time to play out.

Thanks to Neil and Drake University for stepping up on this very important matter of sustainability. Iowans still could control our destiny if we wanted to. I have created a PAC ( Iowa Conservation Voters PAC) with Mark Langgin and Rob Davis to try to influence the composition of our policy makers. We know the problem. We know what to do. Those who have an interest in the status quo control the power centers. That must change if we are going to get meaningful changes in our industrial agriculture sector. There are no limits on water and air pollution and soil loss. There are no controls on the number or concentration of animal confinements. What does Iowa look like if you project recent trends out 10 years? How about 25? The Trans-pacific trade agreement, I suspect, will exacerbate our problems while making a few folks much richer.

Mike, I agree that Neil and the Drake staff did a wonderful job in organizing this conference. It was remarkable.

The requirement of the 1985 Farm Bill for farmers to put in place farm-level conservation plans demonstrated that a flexible regulatory system can work (if we can muster the will to enforce compliance).

Today we are at a similar crossroads for water quality that we were at for soil erosion in the past. And, today we have the water quality database to put together a water quality model (like the universal soil loss equation) that would enable us to create (and require) farm-level water quality plans that would address the N and P water quality problems of each individual farm. Like soil conservation plans, requiring water quality plans would constitute a flexible regulatory system–farmers could choose which practices they wanted, as long as the plan would meet a “T” value for N and P.

We need to keep in mind that nutrient management plans do not adequately address water quality problems. Nutrient management plans ensure that nutrients are not applied in excess of crop needs. But as the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy indicates, optimization of nutrient application will only reduce N loading to Iowa’s rivers by about 10%. Most of the problem of N leaching is related to the inherent N leakiness of annual cropping systems, which have live roots in the ground for less than half of the year.

Francis, thanks for your comment. I am glad you point out the limitations in nutrient management plans. The 10% reduction we get by adopting nutrient management plans is not inconsequential. However if we are going to accomplish water quality, as Iowans, we need to work together. We can only bite off so much. Therefore, if we effectively target and prioritize, it means we will start on the “big ticket” items like wetlands, saturated buffers, no-till, and cover crops. I am afraid that requiring nutrient management plans diverts resources from what we truly need to do.

Francis, I agree that the need for a robust nitrogen model is critical to Iowa and the Midwest. As far as I know, there’s no publically available nitrogen model that’s as robust as Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE2). The only publicly available and “usable” model that I know about is Dr. Jorge Delgado’s Nitrogen Index. And, although I am a fan of the Nitrogen Index, there are a lot of gaps that need to be filled before it can be used to model nitrogen losses in the Midwest. The world of soil conservation is pretty stagnant. It is not like we are coming up with new soil conservation practices to be researched before we can model their effects. In the nitrogen world, it is completely opposite. We have new practices like cover crops, nitrogen stabilizers, foliar applications, etc that greatly complicate modeling. In the private sector, I am most familiar with Adapt-N and I know their research is not keeping up with all these new products and application methods.

Tom, my suggestion is that we build a new model for water quality that is designed to create farm-level WQ plans, much like RUSLE2 does for soil conservation.

The science assessment of the INRS tells us that we already know a lot about the nitrate leaching potential of common farming practices in Iowa, as well as the remedial effects of practices that reduce nitrate leaching, such as cover crops, saturated buffers, etc. It is time to put that knowledge base into a model that will enable farmers to develop farm-level WQ plans that will ensure them that they are meeting the goals of the INRS on their own farms–and I believe it is time to require that of all Iowa farmers.

For decades now we have been investing many millions of dollars in WQ projects–often with great fanfare–but we seem to be no nearer to our WQ goals. I suggest that we invest the next several million dollars in developing the tool that will enable us to meet our WQ goals from the level of every farm in Iowa. That will ensure that we will meet our WQ goals in the aggregate.

A conservative timetable would be to develop the WQ model over the next 5 years, including additional research to shore up weaker data sets ($10 million ?). Then, farmers could be allowed five years to develop and implement farm WQ plans. As additional data came in, the WQ model could be updated (just as USLE evolved to RUSLE to RUSLE2).

The alternative is to continue doing what we have been doing for decades–and getting the same results. My first involvement with water quality was when I worked at USDA and was part of an inter-agency team that launched a National Water Quality Initiative in 1988. Interestingly, that initiative was voluntary, with the caveat that if we didn’t make major progress in solving our WQ problems in five years regulation would be required. 🙂

There was a lot of great discussion last week, I appreciate getting a glipse at all the different viewpoints. I wanted to add one thing to the mixing pot here that I don’t think got mentioned.

So, I’ve inherited my skepticism (read as: bullsh*t meter) from my mom’s side of the family. I’d say it’s also no small coincidence that her side is where all the farmers are in my family tree. So I share the skepticism of regulation being able to fix the environmental issues of agriculture, particularly in its current form, with rules that tend toward one-size-fits-all solutions. However, I also have skepticism of the ability of private business to solve these issues.

In your post, Tom, you quote Einstein’s definition of insanity, followed by a quote from research that shows farmers are hard to regulate due to risk adversity and a belief that addressing environmental concerns hinders economic competitiveness. By this same logic (which condemns the current regime of regulation) isn’t it also insane to expect private industry to solve the environmental problems that are nearly impossible to regulate because of economic considerations? Isn’t the decision to stay in the black in the current year always going to win out over the potential for problems down the road?

Until we, as a society, find a way to address this issue, I will maintain my homegrown skepticism about the real impact that can be achieved.

Tim, I appreciate you skepticism about the private sector. I don’t think they will be truly effective at delivering conservation until we change the “current regime” that you refer to. The private sector is going to make money. That is what businesses do. There is only so much good will the bottom line will support. When the main source of their income comes from selling product, that is what they will do…sell product. But what if we incentivized private business to sell conservation? Along with making money from selling products, what if private ag retailers could profit by working with a farmers to save a ton of soil or to reduce the nitrogen going into our drinking water? Currently we have this system where the public agencies promote conservation and the ag retailers sell product. This automatically sets up a competitive atmosphere. What if we took the public money and incentivized ag retailer? What if ag retailers sold product while at the same time sold conservation? Using this stacked method ag retailers would sell less product and sell more conservation. And, oh wait – we could sell conservation in a more holistic and cost effective way.

Tom,

I think you have gotten to the heart of the matter. Selling Ag conservation may be the key. convince the marketplace that it is to their advantage to do so… not just long term (which ought to be obvious to all) but in the short term as well. There is already a successful movement in this regard within the agriculture arena. Look at the micro markets springing up with regard to “Organic Foods.” Additionally, the non antibiotic issue in chicken flocks (and other livestock). These movements have taken hold in the marketplace due primarily to customer sentiment driving the market economy. Time will tell how sustaining the effort will be but selling conservancy does work.

As manager of the Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification Program (MAWQCP), I’ve enjoyed an interesting daily engagement with this issue for a couple years now that I hadn’t had in my previous private work on the issue. The key overarching comment I’ll make is that my on-the-ground experience with producers (and within state and federal agencies, and among legislatures and congress, and activists) is that there is a very real gap in otherwise specific and concrete nutrient reduction plans. The gap is between setting goals and achieving them. That gap is almost always occupied with reassuring language like “develop implementation” or “activate local plan” or some such, and it may even have some detail that on the surface seems specific and helpful (e.g. 10% conversion to perennial cover, or adopt cover crops, etc.). But I just can’t emphasize enough how that can be really close to meaningless, or useless, when you are standing in the actual watershed and John Smith/Jane Doe farmer needs to know what they have to do to meet the reduction goal/target/objective. The problem is no one can tell them what will result from whatever they tell them to do. If monitoring does nothing else (and it is of course vitally important for a host of reasons), it tells us that we can’t know how to specifically achieve a set reduction. No one knows. Throw in the interrelation of manipulation of neighboring property, and especially weather, any kind of weather, on any given future day of any future year, and nothing is knowable.

But I don’t mean that to be defeatist, I mean to point out that the gap exists, and that it hasn’t been adequately filled. In my work, not having the option to just suggest goals or request someone develop a local plan (we had to justify certification to impart regulatory certainty), we landed on the one thing that was knowable. Ag water quality impacts come from existing pieces of ground and existing management practices employed; there are known risks to water quality presented by conditions and characteristics of actual pieces of land, and from the actual management conducted on that land. And those risks can be identified and they can be treated. But there is no way to know the prescription for a mg/l goal-achieving outcome. Which, of course, is why monitoring is good, it can tell what is happening. But it can’t predetermine any goal or outcome. We need to find and treat the problems, then we can monitor and see what we achieve; a goal is, sadly, technically irrelevant. TMDL implementation plans set goals and suggest actions (use cover crops, install buffers, percentages of watersheds in perennials, etc.), but they ultimately provide no instruction for accurate implementation of goal-achieving actions, practices or structures for a specific farm and its physical land. However, if we identify and remove risks where they exist, the only possible outcome is improvement.

In practice, conducting assessments for MAWQCP certification brings agricultural producers into a conversation with public or private MAWQCP-licensed conservation and agronomy professionals about their resource management, production goals, and stewardship strategies for each and every one of their fields, pasture parcels, or whatever type of land they are managing. This aspect of the process has universally, and predictably, been deeply engaging for producers. These men and woman know the land they farm in greatest detail, have clear goals for managing it, and have an irrepressible curiosity about any advancements or alternatives related to their management of each parcel. And when risks are identified, the assessment process equally engages and empowers them in finding the most appropriate, economical, and effective response for mitigating that risk.

As a result, cost-effectiveness is also an elemental component of MAWQCP certification. Water quality resource concerns are identified literally on a parcel by parcel, crop by crop, and practice by practice basis. MAWQCP certification is whole-farm conversation planning that targets treatment and investment only where and as needed.

In general, I think we all want the same thing. We want crop nutrients to stay where they are applied for the growing crop to use. We want soil to stay in place to feed and support the growing crop. So where is the disconnect? Why is our water quality suffering?

Well, the loss of soil and crop nutrients is hard to see. Sure, you can see the ephemeral erosion that results from a large rainfall event. But, what about the more gradual soil movement that occurs with the smaller rainfall events and with tillage operations? At a quick glance, all soil particles look the same. You can’t walk out into the field and see that a particular soil particle (let alone billions) is now 1 foot further down the hill. The same is true for nutrients. You cannot see them move. Even if you collect a jar of water from the creek, you cannot hold it up and see the nutrients.

We need to quantify losses for farmers. After all, why would they take action if they do not know what they are losing? When you can tell them they are losing 75# N per year and 1” of topsoil every 12 years (just making up numbers here for an example), now you can get their attention. You have quantified their losses. Now they can begin analyzing options to look at improved profitability.

I like to compare this to a house door. It swings open. It closes. It locks. But, is it efficient at keeping the warm air inside the house during the winter? Maybe some new weather stripping is all you need. Or, maybe it is time to get a new door. Well, unless you do a blower door test, you really don’t know how much heat you are losing. But, when you quantify the amount of heat being lost, you can make an informed decision.

What role should the ag retailers play? As the farmers’ most trusted advisors, I believe they need to be equipped with good tools to quantify losses and offer solutions. Our Sustain platform is gearing up to help our retailers do just this.

As a woman farm/land owner with a 300 acre farm located in eastern Iowa along the Mississippi bluff area, I have implemented and practiced sustainable conservation and restorative efforts on my farm for many years. This includes buffer strips, wetland installation, various erosion and soil control measures in my pasture, timber and upper tillable ground areas. These practices have certainly helped control the excessive soil and nutrient runoff and enhanced better water quality measures into the Maquoketa and Mississippi rivers both located near by from the more traditional row crop farming practices used on my farm. But the erosion and runoff has certainly not been reduced at a more sustainable level due to adjoining farming practices and fields next to my farm. That is frustrating and a continuing expense I pay for directly out of pocket or in some small instances with cost share initiatives through NRCS, DNR and other organizations and entities.

I live and work in Des Moines as a professional, certified and educated nonprofit consultant with years in non-profit leadership and fundraising platforms, focused methodologies and profit initiatives. Having served as an Executive Director for 2 state-wide nonprofits in Iowa I know how important it is to reach the passions, pull on the heart strings and reach deeply into donors pockets for support of Missions and Goals.

I believe that we as practicing farmers/land owners, Iowans/consumers need to practice good natural environmental stewardship of our soil, water and air for future generations and legacy capacity building. What I would like to see grow and enhance in conjunction with the agricultural scientific incentives already in place, government programs (of which I participate in), and other descriptives mentioned above in conversations is more or new direct reasons, sources, marketing and public relations efforts that reach into the public/private or consumer sector. People respond more quickly when they are either directly affected by the bottom line, ie. their pocket book, the need to give their children a better future in order to eliminate health/medical problems now ( pocket book) and quality of living. In other words enhancing our message better to the Iowa consumer and perhaps the world, for our need to have their help in funding, enforcing (politically)in achieving better soil, water, air, and sustainability for our natural environment. We can’t do it alone as individual land/farm owners. It’s an effort that has to coordinate and be embraced by all Iowans.

The actual tools for mandatory compliance are already here. Interestingly enough, the regulations were put in place over 30 years ago in 1972 but just not fully enforced, probably for various reasons. Technology is here to be used as an enforcer or as a liberator for the farmer. I would like to see it used as a liberator to help make the farmer more profitable and farming more sustainable. However, in my opinion, to say that it is just a “farmer” problem is really not taking a comprehensive approach. Interesting times!