Many people agree that the nitrogen problem is mostly the fault of farmers, especially since current environmental models demonstrate that agriculture is responsible for 70% of the nitrogen and phosphorus load delivered to the Gulf of Mexico. I could easily be convinced to go along with this narrative. But before piling on farmers, I wanted to take a look at the numbers. Let me share with you what I discovered and the story the numbers actually tell.

As I was looking into the nitrogen numbers, I formed my own baseline – that upper Midwestern farmers will continue to make a living with a corn-soybean rotation. It’s not news to farmers that optimal nitrogen inputs are critical to yields and profits – they get it. Some farmers get it more than others. However, if every farmer uses all of the in-field nitrogen management techniques like right source, right rate, right time, and right place, scientists project that we may reduce nitrogen loading by 6% to 15%. Unfortunately, 15% reduction doesn’t even come close to the 45% reduction in nitrogen loading expected by every state…

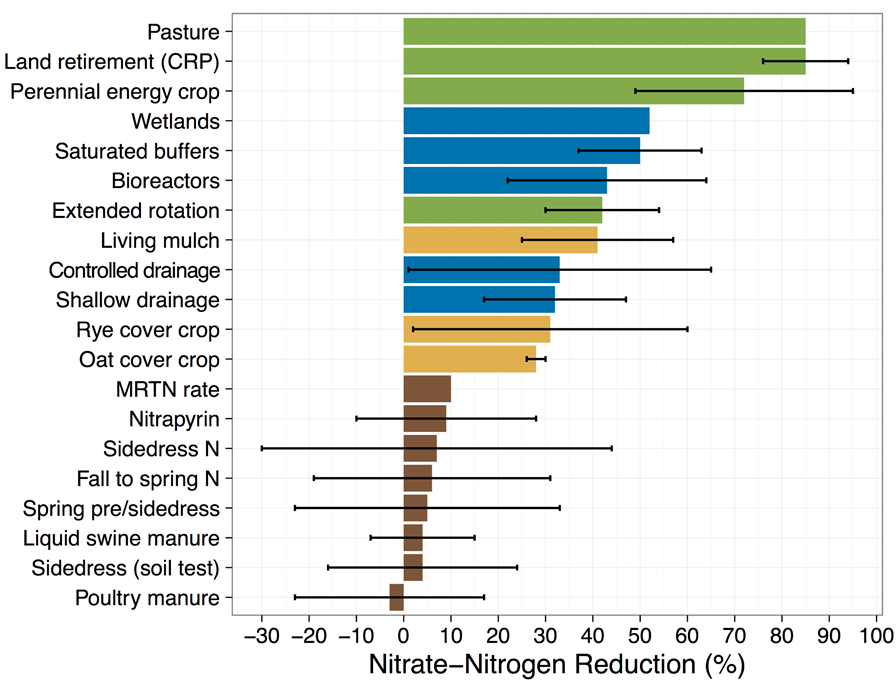

If farmers stick with their corn-soybean rotation over perennial crops, then agriculture has to focus on other nitrogen-reducing practices such as wetlands, saturated buffers, bioreactors, and cover crops to achieve the goals laid out by state Nutrient Reduction Strategies. (Figure #1).

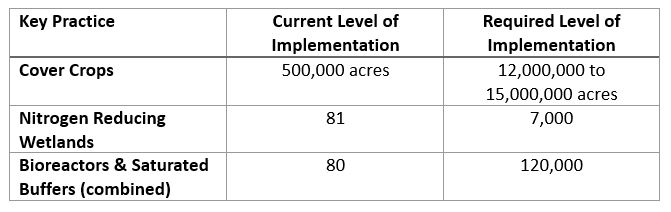

The task of implementing practices to reduce nitrogen is overwhelming when I think about where we are and where we need to be. To achieve Iowa’s nutrient reduction strategy, we need to see enormous gains in nitrogen-reducing practices. Let’s take a look at the numbers we need. Keep in mind, we need to reach the required level of implementation for all practices, not just one practice.

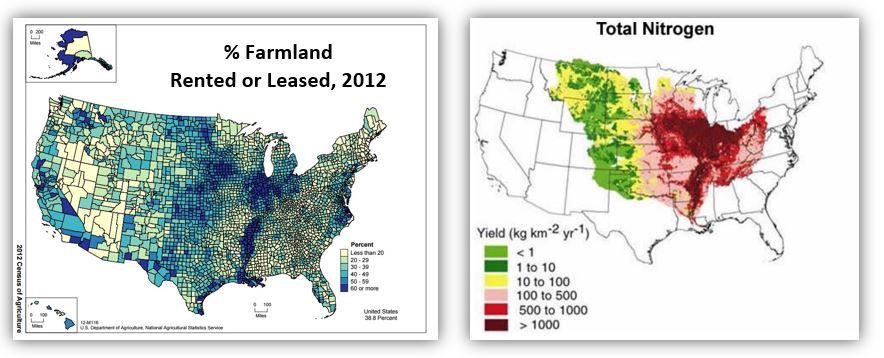

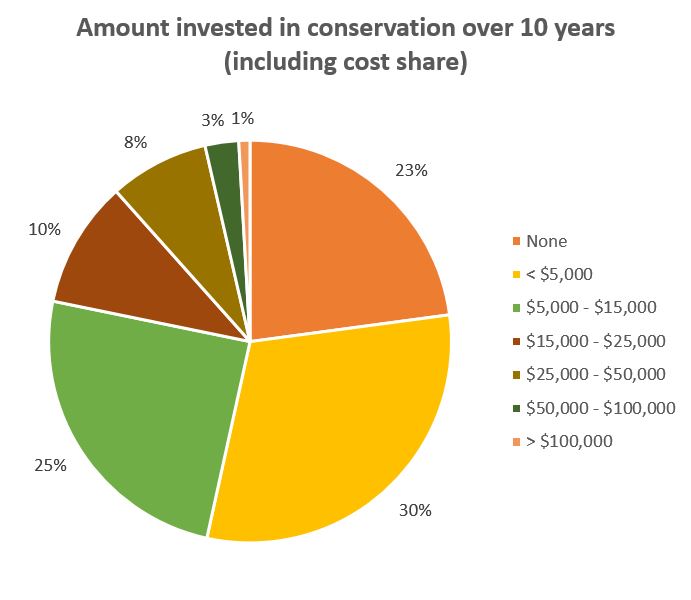

Let’s look at the nitrogen numbers related to land ownership. The U.S. regions with the highest rate of nitrogen loss correlate with the highest rates of non-operator (absentee) landownership. In Iowa, fifty-nine percent of farmland in 2012 was owned by people not currently farming (non-farmers). In other words, 59% of Iowa’s farmland is owned by absentee landowners, also termed non-operator landowners. This is the same land where we need all of those nitrogen-reducing practices I mentioned before. Unfortunately, absentee landowners invest very little money in conservation practices. In 2010, 638 absentee landowners (non-operator landowners) owning land in Iowa were surveyed and asked the following question. “Over the past ten years, what is the approximate total cost of all of the conservation practices that you have established on the farmland that you rent to others? Please consider all expenses, including those covered by cost share or other sources.” It’s interesting to note, that the average landowner surveyed owned 350 acres of land, a value of well over $3 million. This is the data extracted from that survey:

Unfortunately, absentee landowners invest very little money in conservation practices. In 2010, 638 absentee landowners (non-operator landowners) owning land in Iowa were surveyed and asked the following question. “Over the past ten years, what is the approximate total cost of all of the conservation practices that you have established on the farmland that you rent to others? Please consider all expenses, including those covered by cost share or other sources.” It’s interesting to note, that the average landowner surveyed owned 350 acres of land, a value of well over $3 million. This is the data extracted from that survey:

Leasing land can be unpredictable, with many farmers operating on a year-to-year lease or a verbal agreement. In a business arrangement with a short-term lease, how can we expect tenant farmers to install conservation practices that may not guarantee a return on investment, or practices that take years to recoup the initial investment? I don’t think we can expect them to bear this huge financial burden. But I do think we can expect more from absentee landowners. In fact, we can’t solve the nitrogen problem without them.

I am interested in hearing your ideas on this number problem.

Relationships are a funny thing

Relationships are a funny thing

Tom,

In Minnesota as we work with farmers to implement not only better nitrogen management practices but also conservation practices we find this very issue a very important issue. Absentee landowners are usually very reluctant to invest in any conservation practices.

Doug, you are absolutely correct. We must figure out how to motivate absentee landoners. To start with we are doing a pitiful job with any meaningful outreach to absentee landowners. We treat them as they do not exist.

Spot on Tom – well put and succinct. I’d like to share this via my Facebook page, so I’m hoping that’s OK with you and that a link will accomplish that. Thanks for your continuing work on this issue.

Jean, you are more than welcome to share this post. I truly appreciate all of your work with absentee landowners. No doubt there are a lot of people who would be interested in your research and work. It would be easy to change the narrative and say absentee landowners are to blame. However, as you know the conservation community has done very little to engage these absentee landowners. For the most part they have been left out of the conversation.

You blew it two ways. First, controlled nitrogen application during multiple applications (spoon-feeding) with application rates based upon measured need eliminates over application while providing nitrogen as the crop needs it. Second, wetlands (saturated buffers, etc.) fail miserably when they are needed the most and also typically produce NOx, a potent green-house gas 30x more potent than CO2. The chemical process industry learned the value of controlling inputs to minimize/eliminate pollution decades ago. Strangely, the data shows that spoon-feeding nitrogen makes a farmer money – first by minimizing nitrogen costs and second by insuring that the crop doesn’t run out of nitrogen needed for growth/yield.

Lon, thanks for your comment. Your observations are provoking. I would be happy to post any research you can forward my way that demonstrates how spoon feeding nitrogen can have a significant impact on the hypoxia issue. Dr. Matt Helmers, Iowa State University, has shown that even with zero nitrogen application, tile lines still run at around 7 parts per million nitrates. I do not understand how spoon feeding nitrogen to the corn crop can reduce nitrogen to levels lower than when zero nitrogen is applied. Regarding wetlands, research shows that wetlands designed to specifically remove nitrogen produce very little NOx; at least no more than a typical corn field. Furthermore, research demonstrates that these wetlands are very effective at removing nitrogen from the water. I think the jury is still out on NOx levels generated by saturated buffers and bioreactors. Yes, at times, all of these practices pass untreated water through the field, but they still remove a significant amount of nitrogen, and wetlands have the added benefit of reducing downstream flooding…something that is very important to many communities.

https://yosemite.epa.gov/sab/sabproduct.nsf/C3D2F27094E03F90852573B800601D93/$File/EPA-SAB-08-003complete.unsigned.pdf Page 159-160.

“…N2O accounts for a very small fraction of N removal in wetlands receiving non point source nitrate loads, and N2O emission rates from these systems are very low (Hernandez and Mitsch 2006; Paludan and Blicher-Mathiesen 1996; Stadmark and Leonardson 2005). N2O emission accounted for only 0.3% of total N loss in wetlands receiving river flows with elevated nitrate levels (Hernadez and Mitsch 2006), and less 160 than 0.13% of total nitrate loss in a wetland recharged by GW with elevated nitrate levels (based on maximum flux rates reported by Paludan and Blicher-Mathiesen 1996). N2O emission rates in wetlands receiving non point source nitrate loads average around 1 umole N2O m-2 hour-1 (Hernandez and Mitsch 2006; Paludan and Blicher-Mathiesen 1996) which is very similar to rates reported for cultivated crops in the Midwest (1-2 umole N2O m-2 hour-1 (Parkin and Kaspar 2006; Grandy et al. 2006). The available research suggests that wetlands restored on formerly cultivated cropland for the purpose of nitrate removal would have little or no net effect on N2O emissions.”

One tool not discussed, is looking at fertilizer as food. Instead of thinking of nitrogen as nitrate or ammonium, we should be looking at protein, AKA mineralized nitrogen. The Illinois State Nitrogen test measures this. Protein does not leach or volatilize. It can still be found in fields where livestock have not been in 40 or more years. Crops do not respond to additional applied nitrogen. Ammoniaized meat product, that consumers do not want to eat and tankage , that is no longer allowed to be fed, would be a good sources of protein, as well as Asian carp, that are destroying our waterways. Milk that is being dumped, instead of sold, would also be a good source of this mineralized nitrogen.

My favorite definition of insanity “Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. We could do our environment and our profitability a great favour simply by growing corn and soybeans in solid stands. Root systems are larger, involving more soil, absorbing more nutrients, soil is protected by a faster canopy, more biology is supported, water does not know which way to run off the field. The list of benefits continues on and includes higher profit. Marion Calmer said in 2011 ” Corn is a grass and if we want to see it reach it’s full potential we will learn to grow it like a grass! Dr. Bill Dean started me down that path in 2009. Marion is right. We only grow corn in rows because we designed our management equipment around the width of horses and oxen. The machinery exists so why are we persistent in planning and managing around the limitations of livestock? There is a name for it.

Jim, thank you for your comment. It is my understanding that one of the major problems with corn and soybeans is the plant is only alive and growing during a limited time of the year. With the absence of growing roots, the nitrogen leaches below the root zone during the late fall, winter, and early spring. During those months, there is not living root system to pull the nitrogen back to the surface; hence why cover crops are so important. How does planting corn and soybeans in solid stands change nitrogen leaching? I can understand how solid stands might utilize more nitrogen during the summer and early fall, but I don’t understand how it affects nitrogen leaching during the other seasons where this is little to no root growth. I would be very interested to see the research you have demonstrating the positive effects of solid stands of corn and soybeans on nitrogen leaching. Please send it my way.