Historically, cost-share has been awarded to farmers on a first come first serve basis, regardless of the environmental outcomes of the conservation practices. But what if the USDA didn’t base payments on the cost of the practice? What if the incentive payment was based on the performance of the practice instead? By paying for performance versus installation costs, farmers (as well as taxpayers) would have a more accurate way to measure their return on investment.

Conservation program funds are in high demand in the United States, with the number of applications far exceeding the total publicly available funds. To achieve the best outcome for all, conservation agencies must invest public funds in the most cost effective way, while allowing farmers to make their own decisions. In other words, the public should expect to get the biggest bang for their buck and farmers should be able to choose the conservation practices they want to implement. This is not a new idea. It’s been around a long time. I have been mulling over this idea for decades, too.

Back in the ‘80s, a colleague (Roger Wolf) and I even schemed a new method to distribute federal and/or state financial incentive payments for soil conservation. Instead of paying the typical 50% cost-share for soil conservation practice, we wanted to find a way to maximize the conservation dollar. We proposed an incentive program that would pay farmers a flat rate for conserving a ton of topsoil. It didn’t matter whether the farmer installed terraces, adopted no-till, or planted on the contour; a ton of soil was a ton of soil. We thought it genius. Maybe we were right.

The process we devised was simple.

- Determine a reasonable incentive payment for conserving 1 ton of topsoil.

- Calculate the tons of soil erosion reduced/year by implementing the conservation practice.

- Determine the number of acres protected with the practice.

- Determine the lifespan of the conservation practice. For example, terraces may last 10 – 20 years and no-till could be calculated as an annual practice, or as a 5 or 10 year contract.

Let’s look at some pay for performance calculations based on the assumption terraces have a 20 year lifespan. If the incentive payment is $2/ton and the terrace reduces soil erosion by 5 tons/acre/year on 25 acres, the farmer’s payment would be $5,000.

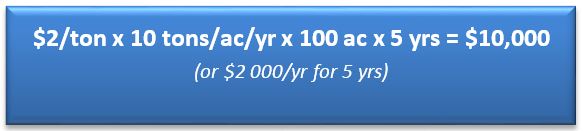

Let’s compare this scenario to a 5-year contract to implement no-till with a cover crop on 100 acres. With the same incentive payment of $2/ton and reducing soil erosion by 10 tons/acre/year on 100 acres, the farmer’s payment would be $10,000.

When we, as taxpayers/farmers/agencies, can realize the measurable result of a conservation practice on soil erosion, cost-share programs become more important and more valuable. Imagine how much more accountable USDA programs would be, if we tied cost-share to outcome measures.

I am quite sure my friend Roger Wolf and I were not the first to imagine a pay for performance system, but at the time it seemed like it. I am disappointed that after all these years, pay for performance has not become the measure by which we dole out cost-share. I think we should begin the transition to pay for performance with a pilot and refine the process for large scale implementation. And I’m sure the public would agree; allocating program funds to get the biggest conservation gain, is most important.

Let’s turn in our old tired system of distributing public incentive payments and work towards a system that encourages efficiency. For more on this topic click here.

(Roger Wolf is now the Director of Environmental Programs at the Iowa Soybean Association.)

The numbers don’t add up

The numbers don’t add up

Tom:

You and Roger were and are correct in the Pay for Performance approach. The real questions are exactly who should participate, and will this work for nitrogen and phosphorus pollution? Targeting those sources of a disproportionate amount of pollution elevates this strategy to the next level.

Hi Pete, yes, this same idea will work for nitrogen. With nitrogen we would need to decide if we want to pay on a reduction of nitrogen that gets into water, nitrogen that is released into the atmosphere as NOx, or both. This is an important distinction. Although I have not done a careful study of nitrogen models I would start by looking at DRAINMOD. DRAINMOD is a computer simulation model developed by Dr. Wayne Skaggs at the Department of Biological & Agricultural Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC in 1980.

The problem becomes, how do you document the amount of soil loss reduction.

I could do my best to get a good cover crop establishment, seeded timely, have it live through the winter, terminate with herbicide(s) and plant with no tillage. Another may not work diligently at establishment, use a minimal amount of seed/acre, have a mix that mostly winter kills, get it seeded late, then terminate with herbicide and till, till, till in the spring. Would we be credited with saving the same amount of soil?

Mark, that is a really good question. There are definitely those farmers that give conservation their full attention and those that do not. The soil erosion models allow for different levels of outcomes. It is the user of the model that has to take the time to input the correct factors to get the correct outcomes. This can be sticky situation. As a user do you model what is on the ground or the effort the farmer put into the cover crop? Sometimes the best plans and efforts to not pan out.

Bingo. Base farm payments on actual performance. Let problem solving farmers figure out the rest.

Karl, I absolutely agree. Choice is good. There is no “one size fits all”. If one farmer wants terraces and the next farmer wants cover crops we should accommodate that, but we should pay on performance of the practice not price of practice.

Couldn’t have said it any better, Tom. How we ever started programs without being performance based has always been a question for me. If you want to incentivize a farming practice, it should always be based upon a result intended by those footing the bill. Taxpayers should be able to demand something for their dollars and likewise those operators integrating a new management tool should expect results. Good editorial.

Thanks Dwight. There simply is not enough public dollars to spend them willy nilly. We need to focus on what gets the most bang for our buck.

Program dollars are not awarded on a first come first serve basis regardless of the environmental outcomes of the conservation practice. Rather conservation dollars are awarded based on priority ranking questions developed by Local Working Groups made up of engaged land owners, land management groups, and other conservation agencies and partners. The ranking questions are resource based and prioritized to address key local resource concerns within geographically described funding pools. Therefore the conservation dollars are awarded according to the priority resource concerns addressed by the conservation plan from which conservation program contracts are developed to fund part or all of the conservation plan needing implemented on the land.

Tom – one way to implement this strategy would be through a reverse auction system whereby you set your target reductions for a watershed (for whatever “pollutant(s)” you are trying to reduce – soil, N, P bacteria, etc.) and then invite farmers/landowners to submit “bids” for practices they want to install. Then run your calculations to determine which ones provide the the best return on the public fund investment to achieve your reduction goals. To add to the cost-effectiveness of this strategy you include in the “bids” how much cost-share they are seeking. This would create an additional incentive to optimize the return on public investment. Highly efficient/effective practices that reduce the greatest amount of pollutant(s) should rise to the top of the list.

Allen, thanks for the comment. I have heard about reverse auctions but I have never seen one work. It seems like this would the reverse action would put the burden on the farmer/landowner to determine the outcome of their proposed practice. Or at least they would need someone to figure the outcome ahead of the auction. It could drive down the cost, but I think it could limit involvement. Regardless we need innovation in conservation. What we are doing is not getting us to where we need to go.

Somewhat related, concerning costs… a few years ago I was asked to write a chapter on NRCS practices. I stumbled on an interesting fact. If terraces were installed on a certain farm that chisel plowed, the payback would be 3 years, and would be approved as an excellent practice. However if the same farm was continuous no-till and terraces were installed the payback would be ~10 years. (Those are not exact numbers, but are representative.) For no-till, the terraces would not be approved, but would be approved if the farmer kept on plowing.

Randall, I agree. Under a pay for performance system the farmer would get paid more for the terrace and no-till option becasue it would reduce erosion even more.

SCS had some ability to pay for performance in the original 1996 Farm Bill EQIP program. Congress took it out of the 2002 Farm Bill. Here is the rational for its removal from the 2002 Benefit Cost Analysis. ___________________________________________

Removal of “Buy Down” Procedures

The new Farm Bill eliminates the “buy down” procedures where operators could improve the offer index

of their applications by reducing the amount of cost share funds they would expect. Removal of this

provision eliminates a facet of the 1996 program that producers found very confusing. This also eliminates

an area of the program that tended to discriminate against smaller and limited resource producers, or those

with less financial resources to cover their share of the costs. These producers were less able to bid down

their applications and as a result were at a competitive disadvantage. However, Limited Resource Farmers

(LRF) were more willing than large producers to buy down on labor-intensive practice costs. The removal

of the “buy down” provisions will tend make the program more equitable for both large and small-scale

farmers and ranchers, by increasing the Federal cost share for all. That increased Federal cost share makes

the Federal funds in EQIP less cost effective than in the 1996 program.

…

“The average financial assistance for each contract has been increased from the historical $8,700 to $13,000 in fiscal

year 2002 and $19,000 in fiscal years 2003 through 2007. This change is due to the fact that the buy-down provision

has been removed, and the anticipated entry of large CAFOs into the EQIP program.”