In my last post I started by saying, “You would think by now that those of us working in the conservation field would have a really good handle on the value of topsoil. Again, you would think… However in 2015 we still struggle with a quantifiable value for topsoil.”

Dr. Rick Cruse’s work gives us a terrific start. However, more research is needed to help us understand variations within fields, across regions and between states because a ton of topsoil does not always equal a ton of topsoil. More research is needed to help us understand why, for example,

- a ton of topsoil affects corn production differently in Nebraska vs. Ohio

- a ton of topsoil affects corn production differently on a hillside vs. a river bottom

- a ton of topsoil affects corn production differently in a dry year vs. a wet year

- a ton of topsoil affects corn production differently in manured fields vs. unmanured fields

- and a ton of topsoil is a lot more valuable on a highly eroded soil than it is in a well-managed, fertile soil.

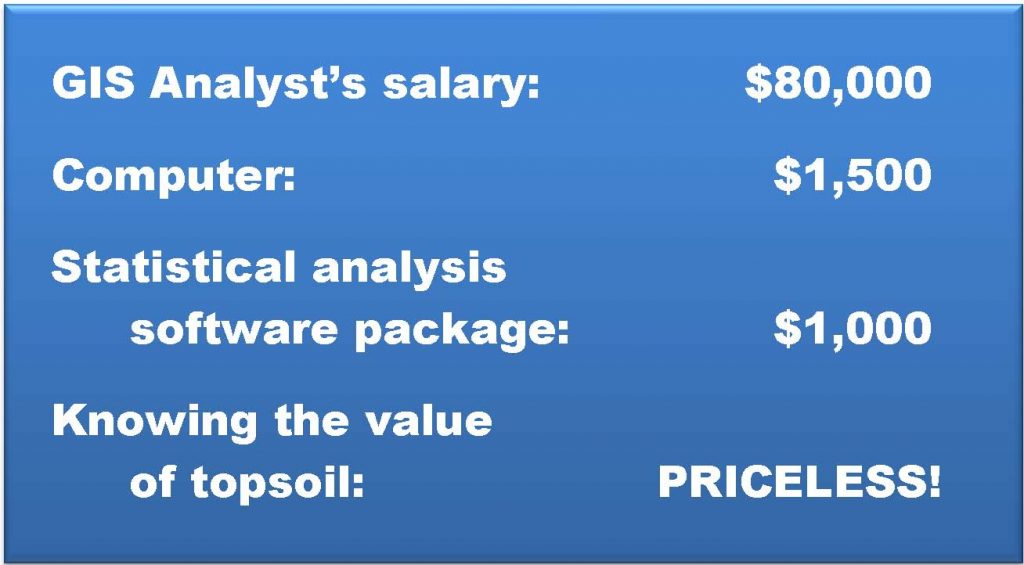

So you get it, right? It is complicated. But it is imperative that we figure it out. Until we start using economic drivers instead of environmental drivers to sell conservation we will make very little progress. And that is why after 80 years of organized soil conservation (1935 to present), we are still dealing with intolerable soil loss. The average rate of erosion considered “tolerable” by conservation agencies is still 20 times the rate at which topsoil regenerates. Clearly, this is not sustainable.

The reason soil erosion continues to be a blight on agriculture is that no one has completely and adequately analyzed the cost of soil erosion. It’s complicated. And it is too complicated for infield research. There are many variables. But, isn’t that the claim of “Big Data” – that if we have enough data, we should be able to figure anything out?

Certainly, Big Data can help us understand how we can affect crop yields by answering questions that were practically impossible to address a few years ago. Site specific data such as rainfall, yields, slope aspect, crop varieties, soil types, organic matter, nutrient levels, and residue levels can be used to drill down through the clutter and make sense of very complicated information.

However, I believe the next breakthrough in conservation will come when someone from the private sector begins to take a close look at correlating soil erosion and yield. Yes it will be complicated, but all agronomic decisions are complicated. Remember in the 90’s when we started grid soil sampling and we thought that if we equalized soil fertility (phosphorus, potassium, and pH) we could equalize or level out the yields across our fields? How did that work out? I think not very well. It took  years for us to figure out how to optimize fertility levels to maximize profitability. Heck, after all this time, we are still tweaking the formula, but we are a lot closer. Imagine what will happen when we unlock the answer to the value of topsoil. Imagine calculating the actual return on investment (ROI) for installing conservation practices whether they are terraces, no-till, or cover crops.

years for us to figure out how to optimize fertility levels to maximize profitability. Heck, after all this time, we are still tweaking the formula, but we are a lot closer. Imagine what will happen when we unlock the answer to the value of topsoil. Imagine calculating the actual return on investment (ROI) for installing conservation practices whether they are terraces, no-till, or cover crops.

In order to really get a handle on the value of a ton of topsoil or inch of topsoil, Big Data companies must get involved. By analyzing big data, we will be able to differentiate the variability in topsoil. Who will be the first data company to take the lead and help us solve the questions? I wonder.

Tom – I appreciate the work to determine the value of topsoil, but maybe we are going at it wrong. Now topsoil is different from a hammer, but what would you tell me if I asked what the value of a hammer is? An economists, of course, would say about $12 at the hardware store. An anthropologist may say it helped build our civilization. A carpenter – maybe a bit of both.

Are we trying to determine the value of topsoil from the perspective of an economist, soil scientist, sustainability supply chain, watershed district, gardening center, carbon trader, public water utility, agronomist, farmer, river dredger, etc?

Given all that you have said about precision conservation over the past year it is becoming increasingly evident that our current level 2 soil survey mapping is obsolete. I would be interested in your vision of what is needed in a future soil survey, if one is needed at all,

Kevin,

I agree the mapping process that was used to develop our current soil surveys lacks some of the detail necessary to allow full integration into precision agriculture. However, I see little evidence there to support remapping of the nation’s soils with traditional methods. Instead, I think it is far more likely that the private sector will use new technology to improve the current soil survey, similar to what DuPont Pioneer has done in partnering with University of Missouri and USDA’s Agricultural Research Service: Pioneer’s Encirca Services. Or another possibility is for the private sector to develop new technology to remotely sense soil properties, creating a new soil survey similar to Trimble’s technology to map soil properties: See more at: Trimble’s C3 Product

Honestly I do not foresee USDA investing a new soil survey.